A FINISHING TOUCH

RESOLVING AN ENIGMA:

Perhaps at this point, the reader of this essay can appreciate the possibility that the plate box contains 1839-1840 portrait experimentation of Dr. John William Draper and Professor Samuel F. B. Morse at the University of the City of New York.

The contents of the plate box continue to inspire meaningful learning and perspective. While reexamining the images recently, Robert Quesinberry discovered a surprising detail concerning the remarkable portrait in plate "J" of Samuel Morse.

Interpreting this discovery requires a review of the lens system that Draper required to create plate "J." This was the second lens system that he utilized from 24 September to about 7 October 1839, consisting of one biconvex non-achromatic lens of four inches diameter and fourteen inches focal length.

Draper explained that by this process:

portraits can be obtained in five or seven minutes in the diffused daylight [indoors]. . . but in the reflected sunshine, the eye cannot support the effulgence of rays. It is therefore absolutely necessary to pass them through some blue medium, which shall abstract from them their heat, and take away their offensive brilliancy."

In plate "J," Morse's eyes were open and clearly delineated though he squinted from gazing into mirror-reflected sunlight. A fulcrum of hand and elbow tightly braced his chin. Even with an extremely long exposure time, Draper's lens only passed enough light to capture a narrow depth of field (blurred nose tip to hazy ear).

Surmounting all these obstacles, Draper still accomplished a distinctive, eyes-open, indoor likeness of the human face. Plate "J" is quite an amazing portrait daguerreotype, but Draper was dissatisfied with the long exposure time and resulting tedium for the sitter. He soon moved on to experiment with other lens systems.

As a preeminent artist and painter of portraits, Samuel Morse was doubtlessly familiar with the problem of tedium for a sitter. Morse was one of few individuals that could have successfully held his position immobile long enough for Draper's second lens system to accomplish plate "J." From this perspective, the daguerreotype was actually the creation of both men. Draper employed his exceptional ability in lens science and Morse contributed his skill and experience as an accomplished artist. As the product of their interaction, plate "J" is truly astounding.

It had previously been noticed that the portrait had a visible anomaly in the area of Morse's mouth. This was generally ascribed to a movement-blur or perhaps a flaw of exposure. Robert was astonished to find that this anomaly seemed to be the tip of Morse's tongue visible in the daguerreotype.

That the extremely narrow depth of field in Draper's image captured part of Morse's tongue was initially rather unsettling. Yet broadening insight resolved the enigma into one of the most evocative facets to emerge from a plate box already overflowing with remarkable visual surprise.

During a lifetime of painting portraits, Samuel Morse had spent excessively long hours in close, exacting, tedious effort. He was probably not the only person immersed in such work who developed a habit of biting on his tongue. This form of habitual reflex is literally a proverbial human expression of intense concentration and attention to detail.

Posing intensely still for five to seven minutes in uncomfortable circumstances would have required exactly the protracted concentration that might have triggered this instinctive habit. Yet Morse could have consciously constrained the impulse. Anyone would reasonably have done this when having a portrait taken. So why did Morse not do so in this circumstance?

The explanation might be found in the now almost unimaginable time before the invention of photography.

Samuel Morse had spent his life immersed in a milieu of portraits, yet neither he nor any other human being had ever seen an exact representation of the human face rendered permanent. Such a thing had never been glimpsed in a painting, a silhouette or an engraving. Morse had observed nothing like it in the distant, eyes-closed "portraits" of full human figures that he had managed to take using his expensive wood and brass camera made according to Daguerre's specifications.

Draper's four inch lens was set in a makeshift tube affixed to something like a cigar box. It was just simply unimaginable to Morse that Draper's portrait technique was capable of recording the distant tip of his tongue in clear focus, so he did not bother to curb the habitual impulse.

Only after holding the daguerreotype in his hand

and turning it in light

would Morse understand that the unimaginable could now be achieved.

The world in which Morse would not have stifled the habit

of biting his tongue during intense concentration,

was extinguished forever by

Dr. John William Drape's portrait of Samuel Morse.

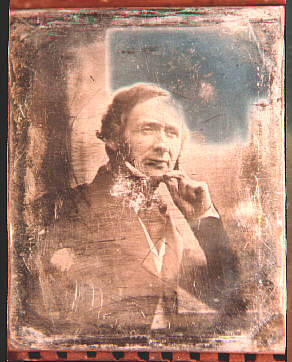

Top: Plate "J"

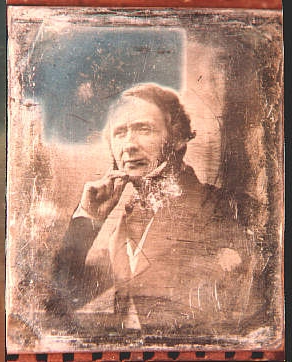

Bottom: Plate "J" corrected