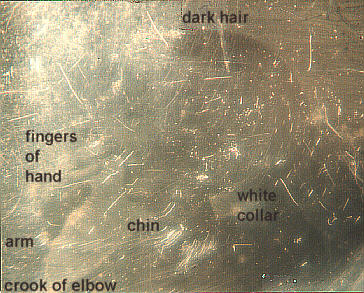

Part of a hand is visible propping up the sitter's head. Dark clothes and hairline, white-spots of the

forehead, cheeks, and chin of the sitter are also visible, exactly as Draper described. Facial

features are shadowy and confused however, apparently owing to a movement blurred or double

exposure of the face.[106*]

|

Detail of Plate

"A" with labels next to areas difficult to see.

[Fig.

26a credits]

|