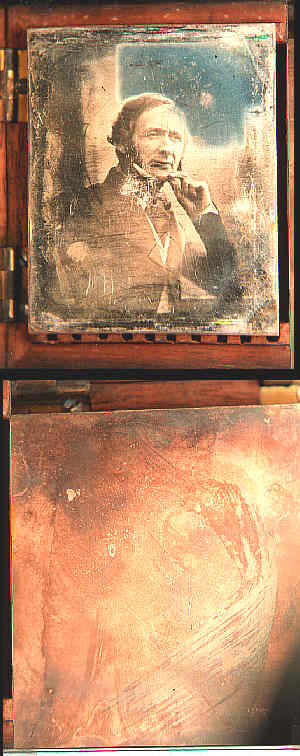

Ninth-plate

daguerreotype Plate "J"

(Writer's collection.)

|

WRITTEN ON BACK: "Milton". The significance of this name is unknown.

For possible

hypotheses see Plate I.

POSSIBLE LENS: This image was possibly taken with the lens John William Draper

describes

second in his sequence of lens experiments to capture a likeness of the human face. Specifically, a

lens

of four inches aperture, with focal length of fourteen inches (about f 3.5). When used indoors

in diffused

light, even with a long exposure of five to seven minutes, such a lens would probably provide

only a

narrow depth of field. The sharpness of this depth of field could be distorted further if the lens was

uncorrected for chromatic aberration (non-achromatic).

Focusing enough intensity of light on the

face to

clearly delineate the eyes and yet not blind the sitter was a difficult problem. Few individuals in

1839

America could have surmounted such obstacles to accomplish this distinctive, eyes-open indoor

likeness of the human face. Just enough depth of field captured sharp detail from blurred nose tip to

hazy ear.

In his own words Dr. Draper described the method he used to accomplish such a true

portrait. Notice that his description of potential defects of operation exactly corresponds with

visual

evidence within this image (the blue stain).

|