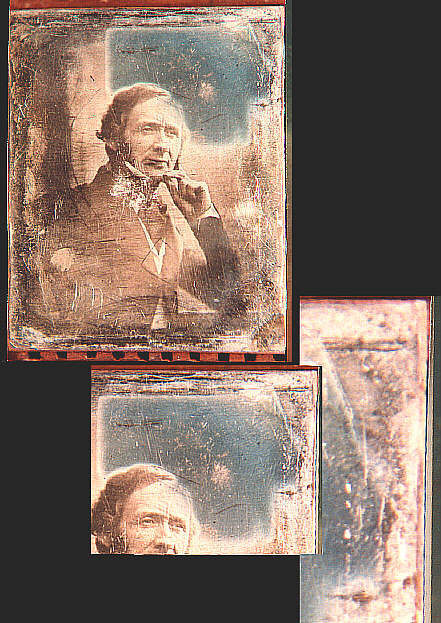

Plate

"J", and enlarged details of what appears to be the

"blue stain corresponding to the

figure of the glass".

[Fig. 17 credits]

|

I have used for this purpose blue glass . . . to permit

the eye to bear the light, and yet to intercept no more than was necessary. It is not requisite, when

coloured glass is employed, to make use of a large surface; for if the camera operation be carried

on until the proof almost solarizes, no traces can be seen in the portrait of its edges and

boundaries; but if the process is stopped at an earlier interval, there will commonly be found a

stain, corresponding to the figure of the glass. [In this daguerreotype a piece of "blue glass"

may have been nailed up in the window opening with a triangular piece of wood at top and a

rectangular piece of wood at bottom. What might be nail heads are even visible in the photo.][58]

|